When We Mourn for Li Wenliang, What Are We Mourning?

Following the death of Dr. Li Wenliang, a writer from China talks about the powerlessness of society to affect change.

By Shouwangzhe (守望者)

Translation by Mr. Almost

This piece first appeared in Matters.news in simplified Chinese and is translated and with permission of the author and publisher.

In mainland China, with its history of autocracy and dictatorship, no minor figure has ever lived and died quite like Dr. Li Wenliang (李文亮). Even before his death was fully confirmed, it was a cause for national concern and mourning.

At about 10:00PM on February 6, the news of Li Wenliang's death spread online. Like many people, I couldn’t and didn't want to believe it was true.

I hoped it was just a rumor. Even though my heart was close to despair, I still repeatedly refreshed the news on my phone, as long as I didn’t see an official announcement, I could still expect a miracle to happen.

But on February 7 at 3:48AM, the Wuhan Central Hospital finally released a formal, official announcement on its Weibo page: “Our eye doctor, Li Wenliang, was unfortunately infected in the fight against the new coronavirus outbreak. Despite all efforts, Dr. Li died on February 7, 2020, at 2:58AM. We deeply lament and mourn his loss.”

There were many people that night constantly swiping their screens for updates on WeChat and Weibo, and their feelings of grief and anger went unabated that night. It was a silent night, but it felt like I could hear the screaming and shouting of the people.

Li was 34 years old. Had it not been for the sudden outbreak of the new coronavirus, he might have remained an obscure, ordinary eye doctor.

On December 30, 2019, Li saw a patient's test report showing a high similarity to the SARS coronavirus. “Because my classmates were also clinical doctors, I sent a message about the virus in a (Wechat) group, as a reminder to my colleagues to be mindful of their own protection.”

Li later wrote on his Weibo account that he did not want to and did not consider himself a hero. He just did the basic human care that ordinary people deserve -- reminding his classmates to pay attention to their own protection.

But what he didn't expect was that on the same day that he issued his warning, the Wuhan City health committee issued an official notice that “no unit or individual shall release treatment information” of the unknown causes of the new pneumonia virus “without authorization.”

Li Wenliang accepted the consequences – he was interviewed by the hospital’s supervision department and was called in to the local police station on January 3 to sign a “letter of admonition.”

Li was joined by seven others who were publicly investigated by the Wuhan police for “spreading rumors” that were later reported on CCTV news.

After three weeks, it was discovered that the eight so-called rumormongers were all doctors. Their good-will reminders to their colleagues broke the iron curtain of secrecy.

After signing the letter, Li Wenliang returned to the hospital to resume his normal duties. Since then, some of the patients he treated were infected with the coronavirus. On January 10, he began to cough, and on January 11, he developed fever and was hospitalized on January 12.

At that time, health authorities in Wuhan and the rest of China were still saying “no human-to-human transmission” and “no medical infection” had occurred.

But with a “letter of admonition” hanging over his head, Li Wenliang did not speak out again.

In the letter, the police said: “We hope that you calm down and reflect carefully, and solemnly warn you: if you continue to be stubborn without any regret, and carry out illegal activities, you will be punished by the law! Do you understand?” (ni mingbai le ma?)

Li Wenliang signed that he “understood” (mingbai) and pressed his fingerprint on the letter of instruction.

The outbreak in Wuhan was fully exposed ten days later, but the best prevention and control opportunity had been missed. Now, the epidemic is still spreading, Wuhan is besieged, the national situation is tense, and no one knows when the black hole of this virus will bottom out.

All the above details are enough to show that Li Wenliang was just an ordinary person. Li is different from 2003 SARS physician Jiang Yanyong (蒋彦永). The latter risked his life, told the truth to international media, broke the government’s information blockade of the epidemic, and almost single-handedly changed the situation of SARS prevention and control.

But Li Wenliang was just one of the many people in our society who lived cautiously. He did not want to be troubled by this incident; the police told him to shut up, and he shut up. He even failed to protect himself and eventually died from the virus.

So why do we mourn him? Why are so many people crying and grieving for this man?

The answer may also lie in his ordinary-ness.

Being a hero is not something anyone can do. How many people can do as Dr. Jiang Yanyong did without hesitation?

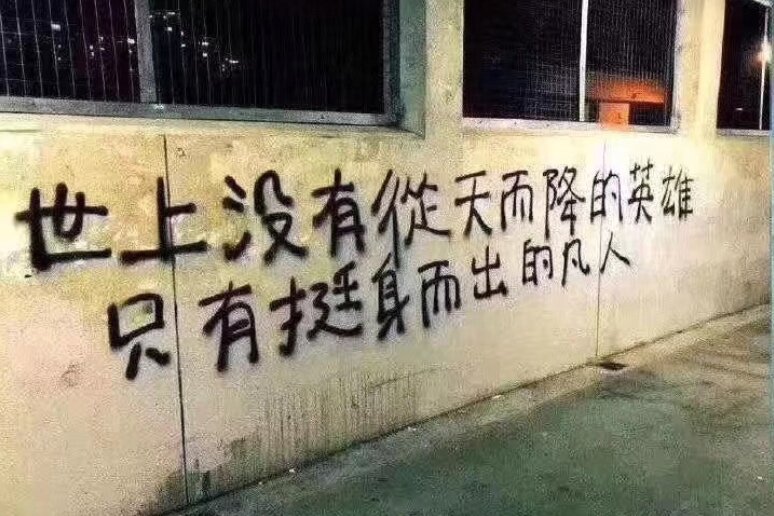

But the vast majority of us ordinary people, can do as Li Wenliang did – when we find that there is something wrong, we will promptly remind the people around us to be cautious; when faced with threats of suppression, we would likely suppress our urges and shrink back.

Speaking publicly to the media after the outbreak was fully exposed, Li was one of only two of the eight “rumor-mongers” who decided to speak out again.

He wasn't sure, however, if he was one of the eight “rumor-mongers” Wuhan Police had discussed on CCTV News. This also shows his sincerity.

“I'm still going to be on the front line after I recover," he told Caixin. “I don't want to be a deserter because the disease is still spreading.”

But Li didn't even get the chance to be a deserter.

This is Li Wenliang, a kind, sincere, optimistic, but timid man. He was a man reluctant to part with his family, a regular doctor who could not escape his upbringing.

He failed to change the course of the epidemic, and eventually died himself.

So, his death is a tragedy of a minor figure. And isn’t the tragedy of such a minor figure not a sign of our own destinies?

Most of us are equally powerless to change the course of the epidemic, or any of the many other social catastrophes that occur.

In the face of government cover-ups, the callousness of officials, the stubbornness of the system, and the decline of society, there is nothing we can do.

Despite our anger, despite the fact that we know it can't go on like this, what else can most of us do but say a few swear words in private and in carefully worded posts on social media?

We didn't actually do anything.

When Li Wenliang's death struck a chord with us, the powerlessness in our subconscious finally exploded. When we cry, we mourn for him and we weep for ourselves.

Li died without an apology from the Wuhan police, or an apology from the Chinese government. In the system's procedures, he died without being “rehabilitated” and left the world with the “disgrace” that he had been reprimanded.

It is a great irony that the grandest things in the system are so false; The police's solemn “letter of admonition” is regarded as Li's best epitaph.

Can the illusion be shattered and the truth be reborn?

I think the answer is still no.

Because we will eventually “calm down and reflect carefully,” and solemnly tell ourselves: “if [we] continue to be stubborn without any regret… [we] will be punished by the law!”

We all “understand.” (mingbai)