Staff from a private vocational high school arrive at the terminal one arrival hall of Taoyuan Airport to welcome the Southeast Asian overseas compatriot students partaking in the 3+4 Program and collect their passports, in July. 29, 2024 (Photo by Yang Tzu-lei).

…(After) The First 10 Years of the ‘3 + 4 Vocational Education Program for Overseas Compatriot Students’

Written by: Hsu Shih-Kai/Hsia Fu-I/Lee Hsueh-Li

Photography by: Yang Tzu-Lei

Designed by: Huang Yu-Chen

Translated By: Brie Harding-Browne

She would go to Taiwan to study, practice her Chinese language, learn valuable skills, and make money── or at least this was the future that 17-year-old Zhao Tingting (pseudonym) had envisioned from her home country in Southeast Asia. Over the past 10 years, 20,000 young overseas compatriot students have come to Taiwan with similar expectations. They came to Taiwan through various vocational programs with guaranteed industry placements which were established by Taiwanese Government in response to declining birthrates, aiming to cultivate and recruit mid-high-level technical workers for Taiwanese industries.

This group of overseas compatriot students from seven different Southeast Asian countries quickly settled in Taiwan. After entering nearly 30 private vocational schools, they were placed into one class despite the huge difference in Chinese proficiency among the students. They moved as a group in their personal and work lives, gradually becoming an invisible labour force that fueled our day-to-day consumer activities, existing in a parallel world to us.

The overseas compatriot students’ pursuit of the Taiwanese Dream and the government’s goal of recruiting more workers should go hand in hand, so where has it gone wrong? Why do these students feel different from their predecessors, more like workers instead? What has their experience been like dealing with the difference in their expectations versus the harsh reality of their education here?

The Silent Faces Around the Town

In August and September, group after group of 16 and 17-year-olds filed into Taoyuan, Taichung, and Kaohsiung Hsiaogang Airports from Jakarta (Indonesia), Manila (Philippines), Yangon (Myanmar), and Hanoi (Vietnam). Waiting to go through customs, many appeared nervous, barely able to respond to the quarantine and customs officers’ questions. The majority did not understand Chinese, and they had varied levels of English. However, they held admission letters for Taiwanese vocational schools, asserting that they had come to study.

These students entering Taiwan are officially classed as ‘Overseas Compatriot Students.’ However, among them are students who do not identify themselves as Chinese, some who do not even have Chinese heritage, and some, though ethnically Chinese, cannot write or read the language.

After passing through customs, the staff members from private vocational high schools across Taiwan verify the students’ identities. They then take their passports to ‘hold in safekeeping’ on their behalf and distribute pre-prepared Chinese name badges and SIM cards. Then the school banner is unfurled and a group photo is snapped, shortly after the students hop on the tour bus and head straight for the dorms.

This has been a common scene at Taiwan’s international airports over the past two years. Each time a group of 40-50, or in some cases over 100, fresh-faced students arrive in Taiwan in an orderly fashion, most in matching uniforms. However, they do not come only to study. A month after their arrival, the schools send them out for ‘work placements.’ Many students end up working in department stores as stock clerks, or as servers in restaurant chains, and housekeepers in five-star hotels. Others find themselves working as assembly line operators in semiconductor and telecommunication factories, or as base-welders for wind-turbines. They have, in turn, become the grass-roots labour force for the service and manufacturing industries in Taiwan.

These students are enrolled in the ‘Vocational Education Program for Overseas Compatriot Students (3 + 4) Industry–Academy Collaboration Class’, more commonly referred to as the ‘3+4 Overseas Compatriot Student Program’.

The program falls under the Overseas Compatriot Student System, and it was launched by the Overseas Community Affairs Council (OCAC) in 2014 in cooperation with the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the Ministry of Labour. The 3+4 Program recruits students aged 16 to 22 years to come to Taiwan, where they first complete three years of vocational high school education, followed by an additional four years of study at a private university of technology. Altogether, they complete seven years of study.

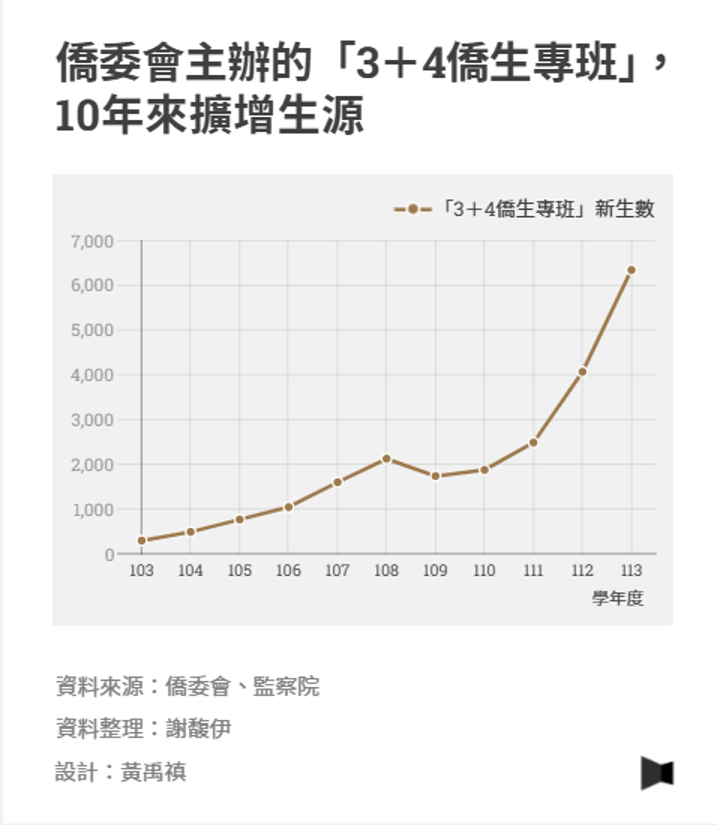

10 years have passed since the program’s launch. In the early stages in 2014 (the 103rd academic year), only 281 overseas compatriot students came to Taiwan. In 2024 (the 113th academic year), there has been a rapid increase with 6,323 new students already enrolled. Initially, only Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand were involved, but this has expanded to now include Vietnam, the Philippines, Myanmar, and Cambodia too. Some overseas compatriots have already been migrated for over one hundred years, and many descendants can no longer speak Chinese, and the connections forged with Taiwan are not as deep as they once were.

The OCAC’s 3+4 Program Student Enrollments Over the Past 10 Years

Y-axis: 3+4 Program New Student Enrollments Number

X-axis: Academic Year

Data Source: OCAC, The Control Yuan

Data compiled by: Esther Hsieh

Graph designed by: Yu-chen Huang

The 3+4 Program assesses student language capabilities to determine admission eligibility, but this has been a huge challenge for overseas students.

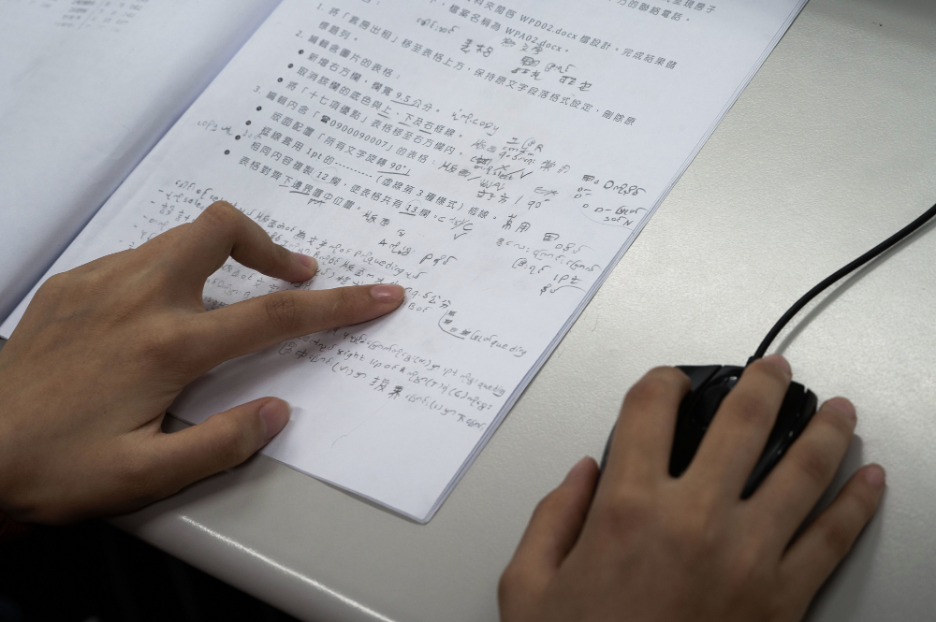

An Overseas compatriot student from Myanmar writes class notes in Burmese at Taoyuan-based Century Green Energy Vocational Senior High School (CGEHS) (Photo by Yang Tzu-lei).

Of the over 20,000 overseas compatriot students who have come from seven Southeast Asian countries, over 80% of them still live in Taiwan.

To better understand their situation, The Reporter sent journalists to various schools around northern Taiwan. In doing so, they found that these students have become an essential labour force in salons and restaurants in the Greater Taipei area. They are usually in small groups, wearing face masks and gathering outside the convenience stores by their dormitories. When we tried to talk to them, most shook their heads and refused to engage. Those with a higher level of Chinese proficiency agreed to be interviewed using a pseudonym, not wanting their schools or employers to find out that their grievances had reached the media.

The students all have different native languages and drastically different levels of Chinese language abilities. Despite this, they are all placed into the same class upon arrival. Before boarding the plane to Taiwan, it is required that all students pass the most rudimentary (A1 level) Test of Chinese as a Foreign Language (TOCFL). In theory, they should have basic conversational abilities. In practice, however, most struggle to even introduce themselves in Chinese.

An unbridgeable gap already exists between the overseas compatriot students and Taiwanese society. While some students openly shared the aspirations they once had for coming to Taiwan with reporters, many others reflected that: “During class, I just zone out, because I can’t understand Chinese.“ Most of them agree that the language barrier is their biggest obstacle.

Wang Tiezhu (pseudonym), one of the students who withdrew from the 3+4 Program, disclosed that the schools failed to set up courses in accordance with the students’ varying levels of language proficiency. He added that the teachers lacked strong communication skills, meaning the quality of classroom teaching was poor. In Wang's class of nearly 50 students, not even 10 of them paid attention; the majority drifted off to sleep or chatted with their fellow classmates.

According to Dong Zhicheng (pseudonym), current student of the 3+4 program, in a poorly executed effort to solve the language problem, the school increased ‘work experience’ hours and reduced time spent in class and studying. They had hoped that this real-world work would suffice as a solution. However, Dong believes that this was a gross over-correction.

Dong claims that some teachers never took into account the comprehension abilities of the overseas compatriot students, lecturing in Chinese at their own discretion. For a motivated student with high language capabilities like Dong, this is manageable enough. Other teachers give up altogether, making the students self-study instead. Dong worries that his progression will lag behind that of Taiwanese students, also feeling that this is unfair for the other students who do not understand Chinese. He believes that if schools think work placement alone is enough and fail to provide solid classroom instruction, “not understanding the coursework or the Chinese language leaves us with the same problem.”

A group of Vietnamese and Indonesian overseas compatriot students prepare to enter the packaging and testing production line on their work placement (Photo by Yang Tzu-lei).

Ke Yuqin, HR operations manager of Walton, had also been under the impression that these students spoke Chinese. “After all, we call them ‘overseas compatriots,’ which has created the misconception that they can at least communicate in Mandarin.” After meeting the students in the flesh, Ke realised that this had been a misunderstanding. She quickly changed her approach, focusing on providing more support, strengthening their language proficiency, and tailoring her teaching materials for students from different countries. This helped them learn relevant equipment and technical vocabulary before starting work in the factories.

However, not everyone is so fortunate as to be assigned to schools and work placements where people actively look out for the students. For the majority of overseas students, studying abroad in Taiwan was not all it was chalked up to be. Before even having the chance to improve their Chinese language skills, they are sent off to work placements. We came across a Taiwanese chef complaining to one of our reporters about one of the student interns while the HR manager wasn’t around: “They do not understand any Chinese, it is incredibly frustrating.”

There is a shortage of grassroots labourers in many industries and trades. In the past, Taiwanese students from cooperative programs between schools and industries were readily available to make up for the shortage. But in recent years, Taiwanese students have abandoned this vocational pathway, leaving overseas students to make up for this gap in the labour market. As the 3+4 Program operates on a rotation-based teaching system, schools must find work placement companies and factories that align with the students’ fields of study, as the students spend three months attending classes and then three months completing their work placements.

Are These Overseas Students Really Our New Professional Workforce? Or Are They the New Grassroots Labour Workforce?

In the early stages of the 3+4 program Tien Chiu-chin, member of the Executive Yuan, was serving as the deputy chairperson of the OCAC. Tien openly stated that the overarching goal of the establishment of this program was to attract overseas compatriot students to Taiwan in the hopes of training them to work as mid-high technical level labourers in the future, while also bringing Taiwan and the overseas compatriot communities in Southeast Asia closer.

“At the time, some members of the Legislative Yuan said that these people are fundamentally foreigners; there is no doubt about that. Legally, they are all foreigners. However, we still need to use our shared ancestry as a means to get them to stay here.”

To recruit students, Tien Chiu-chin previously made the organisers “go to more remote places that we haven't been to before to hold recruitment activities.”

In an interview with The Reporter, Chairperson of the OCAC, Hsu Chia-Ching explained that in the face of declining birthrates the OCAC has redefined the eligibility criteria for determining who is an ‘overseas compatriot’. Originally, the eligibility was determined by the applicant’s ethnicity and ancestry; it is now determined based on Chinese language proficiency.

However, the main issue lies in the massive gap of Chinese proficiency among students. Coupled with a serious labour shortage, some manufacturers don’t even bother with providing proper education and training, instead using the students as ready labourers right off the bat. In unspoken agreement with each other, the schools often transform these students into workers, sending them off to work. The schools strive to fill specialized program quotas to, in turn, recruit more overseas compatriot students.

Secretary-General of the Taiwan Labour Front, Sun Youlian said that he has observed these students working on the same production line for years. After studying up to university level, they still have not learnt any advanced skills, and are treated as replaceable labour by factories and manufacturers. Sun believes that this trend completely contradicts the original intended purpose of the 3+4 Program; it has failed at developing mid-high technical level professionals that are willing to stay in Taiwan.

Sun went further to raise the point that these high-school level students are younger, have a lower Chinese proficiency level, and do not know how to protect themselves. He expressed deep concern for the students’ working conditions:

“Are they (the students) even able to read the contracts that they are signing?”

Shortage of workers in the labour industry. The factories make students fill in fake hours on their timesheets.

Lin Jin-tsai is the Executive Director of the Legal Affairs Centre of the National Teachers’ Union Confederation, and has served as a member of the Ministry of Education’s school evaluation committee for many years. He discovered that some 3+4 Program work placement companies continued to assign students work after the end of their scheduled internship hours by either swapping them to a different work timetable or splitting a single company into two companies: A and B. On paper, students are interns for company A, but student-workers for company B (see footnote). “We often joke that not only is the Ministry of Labour bringing in migrant workers, the OCAC and the MOE are bringing in student workers.”

The Ministry of Education’s Cooperative Education Information website likewise states that companies may not require students to participate in training or work overtime beyond the legally prescribed hours.

If overseas compatriot students wish to take part-time jobs after school or after their internship hours, they must seek a separate legal employer. Under Article 50 of the Employment Service Act, the total working hours for these students shall not exceed 20 hours per week.

Wang Tiezhu’s internship posting at an electronics manufacturer in Taoyuan is an example of this. Wang’s supervisor at the factory often tried to persuade him and his fellow students, saying: “You should work overtime, it helps the company and it helps you”. It may have appeared as genuine care for the students, but in reality, there was no room for negotiation. A Filipino student from the same department as Wang was sent back to the school because he refused to work overtime on the weekends. Their supervisor went so far as to make students fill in fake working hours after doing overtime to avoid inspections by the local labour bureau.

In order to earn more to cover his living expenses during his three-month work placement, and to be in a position to better concentrate on his studies during his three months at the school, Wang cooperated with the company’s wishes, working overtime on weekdays from 6 pm to 10 pm and weekends from 8 am to 5 pm. His overtime hours for a single month exceeded 100. After completing his work placement, he realised that he had underestimated the cost of living in Taiwan. Consequently, he ended up working overtime for his placement and working part-time while he studied. He felt like he had no life outside of work and study, but he had no other option.

It continued like this for two years until Wang decided to drop out of the program and leave Taiwan. Wang is not the only student to have experienced this; fellow students from his school would occasionally complain, saying, “Maybe we should have never come to Taiwan to study in the first place.”

Lin Jin-tsai brought up another example of a Tainan vocational high school which worked with a suitcase manufacturing company. However, when the pandemic hit and production was halted, students were sent to a face mask factory to continue working. “They organised buses to transport the students directly. It was later on that neighbour residents noticed and reported it”. Lin Jin-tsai recalls that when the National Teacher’s Association intervened and investigated, the teacher responsible for the overseas students at the school simply said: “They came here just to make money, how am I wrong?”

“It may seem like the schools hold all the cards. But this isn’t the case. All three parties are in bad positions. The factories have a worker shortage, but aren’t willing to properly invest in workers. The schools, which we had hoped would be focusing on training up students, aren't focusing on education; they are just trying to survive. They want more student enrollments just to keep the school running.”

Shortage of students in private vocational schools. The schools aren’t providing adequate support systems for students, but instead focusing on increasing overseas student enrollment.

CGEHS set up a mechanics department and began admitting overseas students. Their aim was to develop skilled professional welders who were urgently needed in Taiwan’s wind power industry. Principal Chen Kunyu said that they have successfully helped many students obtain welding certifications at various levels. However, he also admitted that launching these specialised classes has been difficult (Photo by Yang Tzu-lei).

Many overseas compatriot students feel disappointed with their study abroad experience. The teachers that oversee the administration have been struggling too. Chen Kunyu confessed that the admission process of these students has been far more complicated than he had previously imagined. “I was aware that our school recruited overseas students, but I didn’t know that there was so much involved”.

In 2022, when ‘Chenggong Vocational High School’, the predecessor of CGEHS, was on the verge of closure, Century Iron and Steel Industrial took over the school’s operations. That same year, Chen, who had taught at several high schools and junior high schools, took a teaching post at CGEHS. The Board of Directors saw value in his experience and hoped that he could improve this dire situation.

As the school has been operating the 3+4 program for a long period of time, of the around 1,100 students, almost half of them are overseas compatriot students. Soon after Chen took over academic affairs, he was asked by the Board of Directors to help in the student recruitment process. He went to Thailand with the OCAC’s joint delegation, where they held a recruitment fair, setting up booths with a number of Taiwanese schools for self-promotion. Chen, who had not come into contact with overseas compatriot students before, noticed that the moment they heard the words ‘free tuition’ and ‘paid internship,’ the students’ eyes lit up.

Chen described the recruitment fair as being akin to “walking around a night market, wherein all of the stalls look amazing.” But these students will weigh their options carefully, so how do we convince them to study here? Chen still remembers the pitch used: “First, the dormitories are fantastic; four people to one room. Second, we are situated in a prosperous and lively area; there are heaps of part-time work opportunities.”

Chen Kun-yu, like staff from many schools in Taiwan, must find new innovative ways to promote their school and market unique selling points. Because of the declining birthrate, the looming threat of closure has become a nightmare for the education sector. According to data from the MOE, 200,000 new students were admitted into senior and vocational high schools in 2023 (112 academic year), a drop of 95,000 from a decade ago.

However, of the 200,000 new students, only around 40,000 were admitted into the 204 private vocational high schools. Among them, 21 schools have fewer than 200 students. The Union of Private School Educators has estimated this year (2024) that within the next three years, 40-50 schools will face closure.

Chen said that there are five key challenges that must be addressed ahead of admitting overseas compatriot students. At each stage, they must meet requirements from the OCAC and the MOE, respectively. These are:

Find a work placement company.

Arrange housing.

Secure enrollment quota.

Travel to Southeast Asia for student recruitment activities.

Take care of the overseas students in Taiwan.

The students are most concerned with the dormitories and work. If the dormitories in Taiwan were low quality and the salary offered and skills taught in the internships did not meet expectations, they would transfer to another school, essentially making the student recruitment efforts a colossal waste.

The Reporter collated enrolment lists from the past six years, finding that in total eight schools had established classes but were disqualified by the OCAC in the following year. Hsu Chia-ching responded, stating that the reason for the disqualification was management disputes and high student dropout rates.

Despite the many recruitment challenges, this year, in the 113 academic year, there are still 28 private vocational high schools operating the 3+4 Program. If a school successfully launches a class, it can then apply for a registration fee subsidy based on the number of students enrolled from the OCAC. They can receive NT$25,400 in tuition fees for each student enrollment. Not only does this create more financial stability, it increases the official student enrollment rate, thereby decreasing the likelihood of being shut down. Chen Kun-yu emphasised that the number of local students is limited, “therefore, the 3+4 Overseas Compatriot Program offers these schools a better chance of survival.”

Further reading:〈東南亞僑生成為私校退場浮木,揭開「搶人」幕後招生大戰〉

How do ‘regular’ schools and work placement companies treat overseas students?

The 3+4 overseas compatriot class at Chung Shan Industrial and Commercial School (CSIC) has students from Vietnam, Indonesia, Myanmar, and more. In an effort to make up for the language barriers, the teachers prepared teaching materials in their native languages (Photo by Yang Tzu-lei).

CSIC is the vocational private high school with the highest number of students currently in Taiwan, with more than 7000. The school has been admitting overseas compatriot students for 29 years, even before the initiation of the 3+4 Program. Liao Jiaxin, the director of the internship office who has been involved with the program for over 10 years, observed that: “Overseas compatriot students have a strong sense of self-respect; they do not want to be treated as migrant workers.” Liao wants Taiwanese people to be more sensitive to this.

CSIC still avoids enrolling too many overseas students, and they strictly forbid overseas compatriot students from working overtime during their work placement period. During the study period, students are only permitted to leave school grounds on weekends to work. Liao stressed the point that students, schools, and workplaces must establish a relationship based on trust. Otherwise, the recruitment of overseas students only serves as a short-term solution, and the sudden influx of student enrollments is more likely to take a toll on the school’s administrative operations capacity.

Of the many overseas students that The Reporter interviewed from all across Taiwan, many brought up the strictness of CSIC, to the extent that even students in Southeast Asia have heard about it. Some graduates straightforwardly said, “I don’t want to go back to those three years.” However, as far as Liao is concerned, this reputation is a mark of success. “Some students are a bit sly; they would say that they want to take on more part-time work. I would tell them that then maybe CSIC isn’t the right fit for them.” Liao’s stance on the matter is firm. He only wants to select students that want to study, not students that just want to work and make money.

Liao Jiaxin told us that in the earlier years, CSIC only had one class for overseas students and that the number of applicants far exceeded the number of spots available. Therefore, the school would test students’ Chinese proficiency. “Back then, we used Mandarin Daily News, getting the students to read articles from them during interviews.” But with policy changes, more schools began enrolling overseas students, and wave after wave of students from Southeast Asia came to Taiwan. Many of the recruitment initiatives focused heavily on part-time job opportunities for students in Taiwan, which subsequently led to students concentrating less on their studies.

Now, when a student asks if they can work more hours, Liao responds: “According to the law, you are only allowed to work a maximum of 20 hours per week. If you work every day, you won’t have the energy to concentrate in class the next day.” Liao has been involved with recruiting students from Southeast Asia for many years; in that time, he has noticed that local overseas compatriot schools and parents observe the Taiwanese schools very closely. “I say to those students and their families: would you go to a school that is willing to break the law?”

McDonald’s has been a part of the 3+4 Program as a work experience company since 2016, and has overseen the work placements of over 1000 students in that time. McDonald’s Taiwan senior HR associate manager Chen Chih-hao disclosed that he has been aware of the overseas students’ long working hours for quite some time, but he doesn’t approve of it. “If you (overseas students) spend half of the night working elsewhere, then return to us exhausted and make mistakes, it becomes my problem. Of course, we hope to work with the schools to ensure better management and communication with students.”

As these students have become a massively important part of the service and food industry, Chen recommends that employers start to rethink their approach. For example, McDonald’s organizes interviews based on students’ Chinese proficiency level, prints workplace manuals in different languages, and arranges for senior students from their home countries to assist newcomers. These measures make students feel valued and supported, which encourages them to stay. In fact, there is already a student supervisor who has stayed long after the end of their work placement through the 3+4 Program for many years under Chen’s management.

“He (the student supervisor) is not only a labourer, but someone who has management skills, is able to communicate with the team, and has already overcome cultural barriers. I believe that this is the kind of outcome that government agencies were looking for.”

We Must Not Repeat the Mistake of Mistreating Migrant Workers

The Migrant Empowerment Network of Taiwan (MENT) marched around Taipei Main Station in a small scale protest, demanding the abolishment of migrant worker brokerage agencies, October. 29, 2023 (Photo by Yang Tzu-lei).

To boost enrollment, private schools have been extensively recruiting overseas compatriot students. However, these schools lack the capacity to provide proper education and support for students, which has been putting the education sector under even more strain. Simultaneously, the National Development Council under the executive Yuan is still striving to reach the goal of bringing in 400,000 workers into Taiwan by 2030, which requires the number of overseas compatriot students to reach 47,000. In response, Hsu Chia-ching has promised to improve the process of verifying Chinese proficiency, thereby improving the students’ learning abilities. Hsu also promised to lessen safety risks during internships and work towards reducing communication breakdowns between students and school administrations.

In regards to the issue of students working overtime, Hsu stated that the OCAC will increase surprise inspections of schools and companies to prevent them from showing off ‘model students’ and covering up illegal practices. “When I arrive and the students have already gone off to work, it won’t be possible to suddenly bring them back.”

Sun Youlian, Secretary General of the Taiwan Labour Front, is one of the earlier overseas compatriot students who came from Malaysia to Taiwan to study in 1992. Influenced by the wave of democratisation Taiwan was experiencing, he became heavily involved in the labour movement, remaining an active member to date. In Sun’s view, “The schools need to make major improvements on their end to address the failings of the 3+4 Program. After all, the identity of these students is learners; the students must first complete their studies in the 3+4 program, and then they can enter the workforce.”

How can the government fix this? Sun suggests that as the relevant regulations come under administrative law, action can only be taken against the schools if the individuals affected file complaints themselves. However, governments can be more proactive by using policy tools, such as reducing subsidies and incentives to push schools to make improvements on their own accord. Sun argues that evaluation of each school’s program implementation should not rely on enrollment figures. Rather, the quality of teaching needs to be closely scrutinised. According to Sun, these measures will be much more effective than labour inspections.

“All developed countries are facing declining birthrates. Should countries try to draw in students and immigrants? Yes, they should. But how should they go about it? I believe that our country has not had a clear goal.” He went further, saying that Taiwan needs to come to a consensus on the future of new immigrants and migrant workers. We need to face the reality of the changing demographic landscape and open ourselves up to new solutions.

Sun expressed concern over Taiwan’s previous maltreatment of migrant workers and international students, which left an international notoriety for human trafficking. All in all, the 3+4 program demonstrates that Taiwan’s attitude as a whole needs improvement. “If our overseas students are treated as migrant workers have been in the past, continually undermining their rights and interests, of course they won’t want to stay in Taiwan.”

“It is always about the people. The labour force is people. When we don’t treat people well, problems arise.”

Note: According to The Act of the Cooperative Education Implementation in Senior High Schools and the Protection of Student Participants’ Rights, the daily “training hours” for overseas compatriot students working at internship companies may not exceed eight hours.